Violence and political instability caused Mexicans to seek refuge and work in the US. Thousands arrived each year, leading to a surge in migration.

During World War II, the US faced labor shortages, which led to the Bracero Program, which allowed Mexican workers to enter for a period of time for agricultural jobs and labor work. While it provided opportunities, it also led to exploitation and discrimination.

Nationality-based quotas were removed by the Hart-Celler Act of 1965, leading to changes in migration patterns. Although indigenous peoples began to refer to Mexican immigrants as “illegal aliens”, after 9/11 they faced deportations and increased securitization policies.

Today, one of the biggest issues in the region is migration, including discussions about DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), border security, and the economic impacts it has on the region.

Los Angeles and other southwestern US regions have Mexican roots 1. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 allowed many Mexicans to identify as American without relocating, highlighting the fluidity of territory and identity.

Mexican labor recruitment began in the 1890s. Political instability caused by the Mexican Revolution triggered large-scale northward migration, with strategic planning to set up future movement.

Established during World War II, the US-Mexico Labor Agreement was a bilateral program aimed at managing temporary agricultural labor migration. California was a major destination for these workers.

Many Mexican agencies administered the program. Although some hoped it would spur development in rural Mexico, some internal opposition led to domestic labor shortages.

Despite official channels, corruption in the selection process – such as fraudulent paperwork and contract selling – was widespread. Local power often decided who was selected, reflecting tensions and reconciliations between conservative factions and reformers.

Migration was political. Agrarian reformers, the Catholic Church, and conservatives used the Bracero Program to advance social agendas. Selection reflected deep community-level divisions, especially in midwestern Mexico.

US farm workers’ organizations, civil rights groups, and media houses criticized the program for enabling the misuse of funds by depressing wages. All these reasons led to the program being closed in 1964.

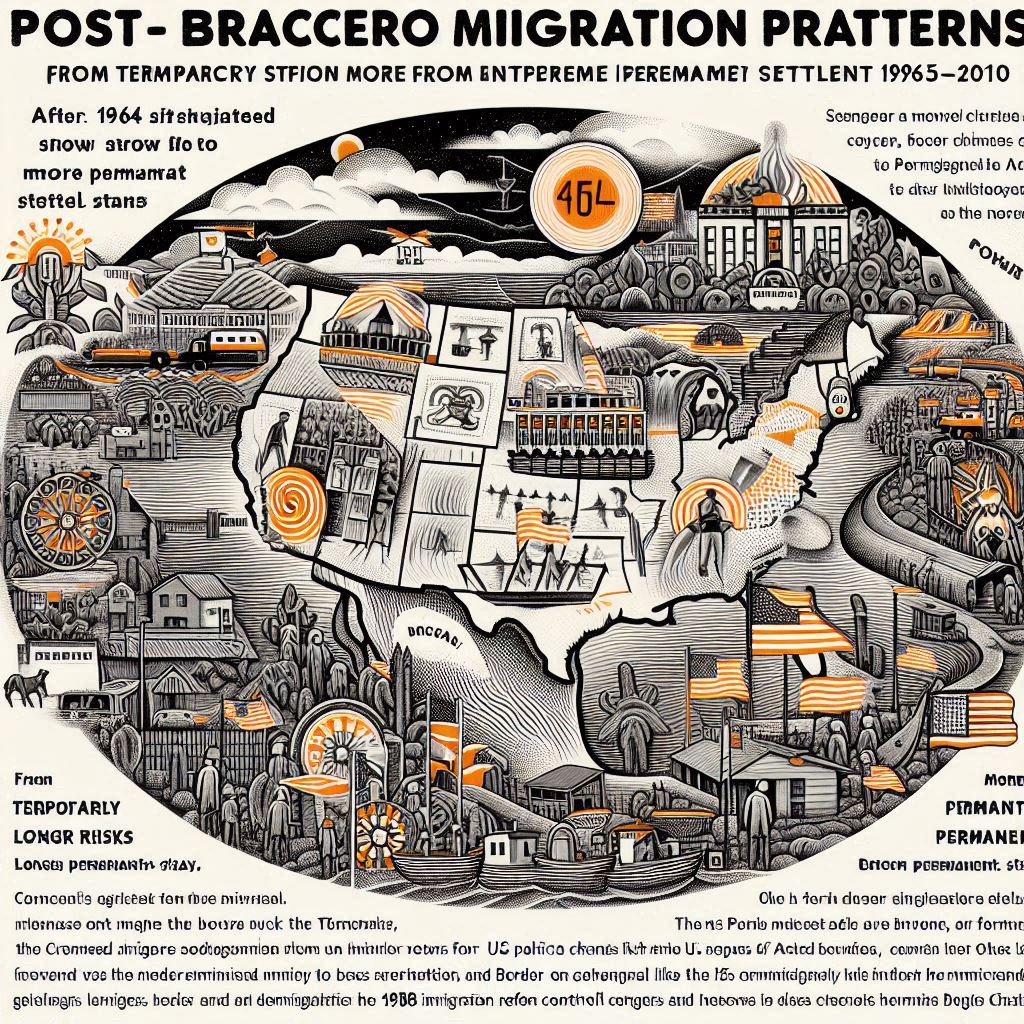

After 1964, migration changed from cyclical to more permanent settlement. Such was the case with border risk, longer stays, and the 1986 election. This was due to US policy changes such as the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA).

A shift was observed in the second half of the 20th century: circular workers in the 1960s-70s, distress migrants in the 1980s, and families including more women migrating when legalization became possible in later decades.

The IRCA legalized many people, but also imposed restrictions if they could not find work. Despite these reforms, undocumented migration increased. Economic inequality increased as wages for illegal and legal workers differed.

The biggest drivers of changing rural employment were liberalization policies such as NAFTA and Mexico’s economic recession, which spurred migration. Trade benefits were not equitable, displacing workers in traditional industries and small farmers.

Migrant networks facilitated new migrants by providing support and reducing risk in the US. Many migrated not only for money but also for family reunification and personal freedom.

While midwestern Mexico remained a major source, migrants began to flee northern border cities and Mexico City, and moved to new, less traditional destinations across the US.

Since the 1990s, the US has expanded border surveillance with more security officers, agents, walls and surveillance. Some policies have focused more on interior enforcement – targeting undocumented migrants who had already settled.

Stricter border regulations have not deterred migration, but have forced people to take riskier routes. Some enforcers have turned to smugglers or bribed officials, increasing the risk of exploitation and violence.

Since the early 2000s, net migration has slowed and even reversed. Some factors include the US recession, economic recovery in Mexico, a declining youth population and job availability.

The migrant experience has been shaped by organized crime. People fleeing cartel violence face kidnapping, extortion, and recruitment by gangs. Migrants are often caught between coercion and survival.

Anti-Mexican attitudes predate modern politics in the US. Policies such as California’s Proposition 187 and events such as the Mexican–American War reflect long-standing hostility Mexican immigrants face.

Discriminatory laws have historically fueled resistance among Latino communities, prompting protests, civic engagement, and legal challenges to protect migrant rights and dignity.

Migration from Mexico to the US is not a new phenomenon—it is a social, political, and historical process that is steeped in both hardship and opportunity. From the Bracero Program to racial politics and border militarization, the story of Mexican migration highlights the complexities of labor, identity, and human aspiration. Effective migration governance requires more than border control; This requires historic policy reforms, humane behaviour and awareness that respects their rights and contributions.